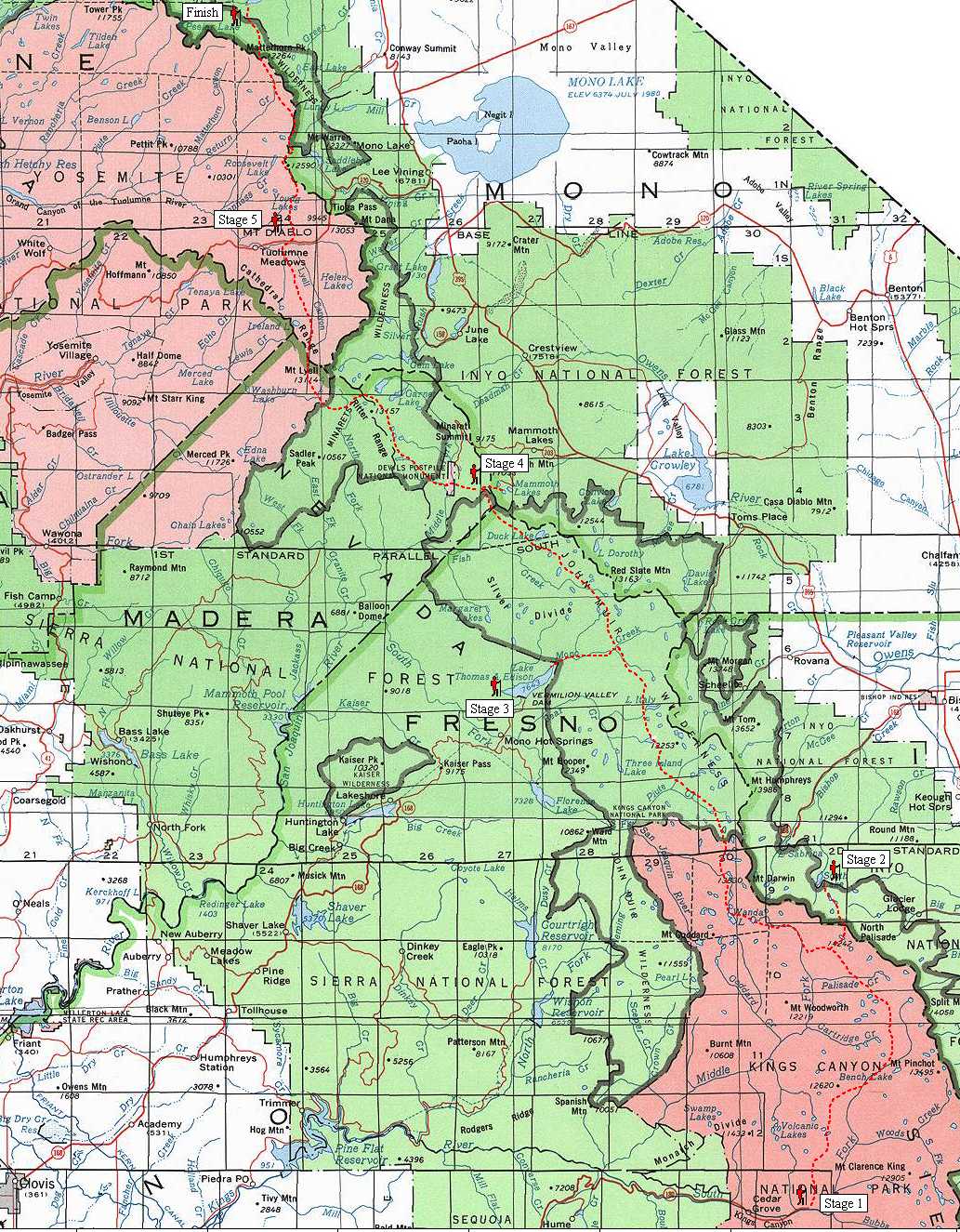

Sierra High Route 195M Backpack Road's End to Mono Village, California

The SHR is a 195-mile trekking route that runs north-south through the heart of the High Sierra, the crown jewel of the Sierra Nevada Range. It passes through two National Parks—Sequoia-Kings Canyon and Yosemite—and two wilderness areas—John Muir and Ansel Adams. It is a rugged alternate to the John Muir Trail (JMT), boasting about 100 miles of cross-country travel, numerous Class III scrambles, and seemingly endless miles of boulder fields. SHR hikers are rewarded with pristine alpine settings, uninterrupted stretches of solitude, and a sense of true adventure. The route was developed by climber Steve Roper back in the late-1970’s. Starting and Ending Points The southern terminus is at Road’s End in the South Fork of the Kings River, about 90 miles east of Fresno. Its climbs into the high country via the Copper Creek Trail. The northern terminus is at Mono Village, at Twin Lakes, just outside of the northwest boundary of Yosemite National Park, about 13 miles southwest of Bridgeport. If you do not wish to hike the entire SHR, it is possible to do it in sections, though because the trail is so remote and because vehicle access is so limited, this is logistically difficult and often involves hiking long distances from nearby trailheads before the SHR is even reached. But, in that sense, portions of the SHR can easily be integrated into loop hikes. SHR versus the John Muir Trail The SHR and JMT are of similar distance (195 for SHR, 218 for JMT) and both go north-south through the High Sierra. Additionally, the SHR uses about 30 miles of the JMT corridor. But otherwise the trails—and the experiences they provide—are markedly different. First, the SHR is not an official trail; it is a route. It is not labeled on any maps and there is no signage for it on the ground. Very few people know about it, and even fewer hike it. It is not a continuous footpath—about half of its length is off-trail. In almost perfect contrast, the John Muir Trail is an official trail; it is labeled on maps and there is signage on the ground; lots of people know about it and hike it; and it’s a continuous footpath. Foot Traffic It’s estimated that about 10 people hike the entire SHR each year, i.e. thru-hike it. There may be more or less, but—whatever the exact number may be—it’s small. Like all long-distance trails, it receives more traffic from section hikers (and, perhaps in the most accessible portions of the route, day hikers). But, again, this traffic is peanuts compared to elsewhere in the High Sierra. When to go The optimal time to hike the SHR depends on your hiking skills and preferences, and the particular year. For all but the most experienced mountaineers, the SHR is probably off-limits from November through May—the avalanche dangers, stormy weather, and snow-related issues make the winter very risky. Of course, if it is a particularly heavy or light winter, the conventional hiking season may be longer or earlier. Early-season hikers (June and July) will experience more snow, more wet feet, and more mosquitoes than hikers later in the year. Hikers in August and September will experience drier conditions and few mosquitoes, but the melted-out mountains will not look as majestic and the scree fields will be more exposed. Hikers in October will experience the driest conditions, the coldest temperatures, and the fewest bugs. Direction Your

direction is non-critical unless you are hiking early or late in the

season. If you are going early, you’ll want to go north: the

southern sections of the route receive less snow, and it’s easier

to walk down the snow-holding north-facing slopes than to walk up

them. If you are going late in the season, you’ll probably want

to travel south: the northern sections of the route are more likely

to get whacked with snow first. If you are not travelling early or

late, then you can chose to either way. Buzz and I went north, mostly

for logistical reasons: it was easier to extract ourselves post-hike

from Mono Village than it was from Road’s End. But I preferred

this direction anyway: the sun was at our backs, making for better

photos and less sun exposure on our faces; and most of the passes

have gentler south slopes than north slopes, which made for easier

travel. In order to reach Road’s End, which is just west of the historic town of Kanawyers, we flew into Fresno (FAT) from Denver and found a shuttle driver via Craig’s List to drive us the 85 miles. I offered $60 + gas (about $80 total) and received about five emails from available drivers within 30 minutes; you could probably ask for less and still find someone. After we reached Mono Village and washed up in the lake, we hitch-hiked into Bridgeport with one of the many Mono car-campers. From Bridgeport we took the CREST bus directly to the Reno (RNO) airport; it cost $17 one-way, which is a great deal. Bears There are black bears in the High Sierra, lots of them. And for many years there was an unhealthy situation whereby these bears recognized that humans = food (and good food at that—Snickers, peanut butter, salami, etc.) and proceeded to regularly outsmart the humans who tried to protect their food by hanging it, burying it, and even sleeping next to it. Bears are not interested in humans, but they are interested in our food, and this is partly why bears are a major management consideration in the Sierra. (That, and because frankly they have the potential to easily kill you). Bear canisters Bear-resistant canisters are mandatory in most places throughout the High Sierra, including many places through which the SHR passes. I hate bear canisters. They are heavy (1 lb, 15 oz for the lightest model, the Bearikade Expedition from Wild-Ideas), they are an added expense, and they are uncomfortable to carry (their cylindrical shape fits awkwardly in small packs, and their hard sides inflict bruises if not cushioned correctly). Moreover, I would argue that canisters are not necessary if you practice good bear country techniques: do NOT camp where you cook, do NOT carry overly smelly foods or items, and do NOT camp in established sites or near popular trails; DO stealth camp, DO carry your food in odor-proof bags, and DO burn your trash every few days in order to minimize odors. Bears are most problematic in high-traffic areas, which the SHR purposely and mostly successfully avoids. However, if you are caught by a ranger and you are not carrying a canister, you can receive a hefty fine. Rangers do patrol the backcountry, though in lower frequency than they used to (thank you Bush administration), and they regularly do canister checks on passing hikers. I’m not aware of any guaranteed technique to avoid a fine, e.g. by raising legal technicalities against warrantless searches or questioning law enforcement jurisdictions, etc. Therefore, my recommendation is to carry a canister—not to protect your food from bears, or to protect bears from you, but to protect yourself from rangers. If rangers were not out patrolling, I would not take a canister and I would instead rely on the effective techniques I have described above. Buzz and I both carried canisters. For more information, visit the following land manager websites: Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park, Yosemite National Park, and Inyo National Forest. Permits If you start the SHR from a terminus, you will need a wilderness permit. The High Sierra is managed by several agencies, but you only need a permit from the agency that manages the trailhead from which you are starting. If you start at Road’s End, you will need a permit from Sequoia-Kings Canyon NP; they detail the permit system on their website. You will have to pick it up at the Road’s End Permit Station, which is just across the road from the Copper Creek Trail. If you know your starting date 14+ days beforehand, I would recommend that you reserve your permit ahead of time—it’s worth the $15 reservation fee to guarantee your access to the SHR. If you do not reserve your permit beforehand, approximately one-quarter of the permits are available on a first-come, first-serve basis. Visit this page to check availability. Buzz and I had no issues in early-July obtaining a permit via the walk-up approach, though if we had prepared earlier we would have reserved a permit to avoid the risk. Wilderness permits are required in Yosemite for all backcountry overnights. Visit their website for more information. I am not as familiar with that system—e.g. where to pick up your permit, their reservation policy, etc. so I will not comment. Depending on the time of year, Inyo National Forest—which manages the Ansel Adams and John Muir Wilderness Areas—requires overnight users to obtain a free wilderness permit. Again, I am not as familiar with their system; visit their website for more information. Gear The most appropriate gear for your SHR outing depends on the season, your personal experience and skills, and your preferences. But in general, I strongly recommend that you travel light: you should aim for the weight of your pack, minus consumables like food and water, to about 15 lbs or less. For backpackers raised in the classic style—i.e., those who follow the motto “Be prepared” to the nth degree, or those who are still sporting their vintage 1970’s Kelty external frame pack, giant bedroll, and stainless steel Sierra cup—this goal may seem out of reach, but I assure you that (1) it’s not and (2) it’ll greatly improve your experience on the SHR. Traveling light on the SHR is even more important than on a standard backpacking trip. Here are a few reasons why… (1) The SHR features many steep passes, many big climbs, many Class 3 scrambles, many miles of boulder fields, and constant exposure to thunderstorms. A lightweight pack will reduce the stress & strain on your body and improve your mobility, thus reducing your risk of injury and your long-term wear on important body parts like your knees. (2) There are few convenient places on the SHR to resupply so you’ll have to carry a lot of weight in food. Heavy pack + lots of food = slow, hard, and uncomfortable. Also, by reducing your base weight you can hike more miles per day and cover the distances between resupply points quicker, which will reduce the amount of food weight you must carry. (3) The SHR goes through some very remote country that is not well suited for search & rescues or easy self-extraction. Acute and overuse injuries are more likely with a heavy pack, which frankly makes them downright dangerous. Finally, (4) the SHR demands a high level of mental engagement in order to navigate efficiently and to travel safely. A heavy pack increases mental fatigue and makes these tasks more difficult. Resupplying Generally, I prefer to resupply by sending packages to myself via the mail, as opposed to trying to gather supplies in town. This system is more time-efficient and it ensures that I have everything I need/want. I recommend this system especially for the SHR because there is only one convenient opportunity to buy supplies en route—at Tuolumne Meadows, where there is a small grocery store about two miles down Tioga Road. But Tuolumne is located about 168 miles north of Road’s End and 27 miles south of Mono Village—hardly halfway—so it does not help much in reducing the amount of food that must be carried. The better location at which to resupply is Red’s Meadow, which is located about 118 miles north of Road’s End and 77 miles south of Mono Village. Red’s receives a lot of resupply boxes from John Muir Trail hikers and they have a good system in place; the fee is $25/box. There are other locations to resupply but they are not nearly as convenient: to reach Bishop, hike over Piute Pass to a trailhead on the east side of the Sierra crest and then hitchhike into town; and to reach Mammoth Lakes, take the shuttle bus from Red’s Meadow or hike into town from Mammoth Pass.

|

2017 October 1-8

Description of the Sierra High Route - per Andrew Skurka

2017 October 1-8

Description of the Sierra High Route - per Andrew Skurka